Tips & Tricks

5 min read

2026 Could Mark the Start of a ‘Jobless Boom,’ Warns AI Pioneer Geoffrey Hinton

One of the world’s most influential artificial intelligence researchers is warning that the global economy may be approaching a turning point where growth no longer translates into jobs.

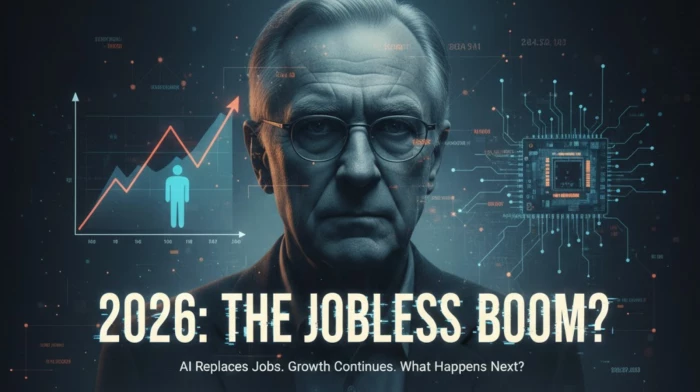

Geoffrey Hinton, often referred to as the “Godfather of AI,” said in a recent interview that 2026 is likely to be the year a “jobless boom” begins, driven by rapid advances in artificial intelligence that allow companies to increase productivity without expanding their workforce.

The warning comes as AI systems already outperform humans in a growing range of cognitive tasks, from customer support to data analysis, and are beginning to reshape white collar work at scale.

Hinton’s concern is not about economic collapse. Instead, it is about a disconnect between economic growth and employment.

In a jobless boom, companies become more profitable and productive while hiring stagnates or declines. AI systems absorb tasks once handled by people, allowing firms to produce more output with fewer workers. The result is rising GDP alongside falling job security.

According to Hinton, this shift may arrive sooner than many policymakers expect. He argues that AI capabilities are improving at an accelerating pace, with systems now able to handle increasingly complex work over longer time horizons.

Hinton has pointed to a pattern he sees in AI development. Tasks that once took humans minutes to complete are now automated, followed quickly by systems capable of handling work that spans hours, days, or longer.

If that trend continues, he says, 2026 could be the year AI reliably replaces “many, many jobs,” particularly in roles built around repetitive intellectual labor. Unlike earlier waves of automation that targeted physical work, this phase directly challenges jobs that rely on reasoning, language, and pattern recognition.

Hinton has compared the moment to the Industrial Revolution, when machines diminished the value of human physical strength. This time, he argues, AI threatens to reduce the economic value of human intelligence itself.

Some economists say evidence of this shift is already visible.

Large companies have begun citing AI driven efficiency gains while announcing layoffs or hiring freezes. Firms are increasingly allowing headcount to shrink through attrition rather than expanding teams, even as revenues grow.

Research cited by labor analysts shows a sharp drop in entry level white collar job postings since the widespread adoption of generative AI tools. Positions in administration, customer support, junior software development, and basic data analysis appear especially vulnerable.

Several studies estimate that more than 10 percent of current jobs in advanced economies are already technically automatable, with that number expected to rise rapidly over the next two years.

Experts broadly agree that roles built on predictable, rule based tasks are most exposed in the near term.

These include call center work, back office administration, data entry, basic accounting, and junior coding roles. AI systems can already handle much of this work faster and at lower cost than human employees.

Retail operations, warehouse management, and some creative tasks such as basic graphic design are also being affected as automation tools improve.

Hinton has stressed that this does not mean every worker in these fields will lose their job, but it does mean fewer new jobs are likely to be created, especially at the entry level.

Some economists and industry leaders argue that AI will ultimately create more jobs than it destroys. Forecasts from organizations like the World Economic Forum predict millions of new roles emerging in areas such as AI oversight, healthcare, education, and advanced engineering.

They point to historical precedents where new technologies disrupted labor markets before generating new industries.

However, Hinton and others counter that this transition may be unusually painful. The pace of AI adoption could outstrip the speed at which workers can retrain, leading to prolonged periods of unemployment or underemployment.

Beyond economics, Hinton has warned about the social consequences of large scale job displacement. Work, he argues, is closely tied to dignity, purpose, and social stability.

He has called for governments to prepare now, through large scale reskilling programs, serious discussions about income support systems, and stronger regulation around AI deployment. Without intervention, he warns, wealth could become even more concentrated while millions struggle to find meaningful work.

Hinton has been careful to stress that a jobless boom is not inevitable, and that his warning should not be read as a declaration that mass unemployment is unavoidable. Instead, he frames 2026 as a potential inflection point, one shaped by decisions that governments, companies, and regulators are making right now. How AI is deployed, governed, and integrated into workplaces over the next two years will play a decisive role in determining whether productivity gains translate into broad social benefit or deepen economic inequality.

He argues that the danger lies less in the technology itself and more in the speed and incentives surrounding its adoption. Companies face strong pressure to cut costs and increase efficiency, which can make replacing workers with AI systems an attractive short term strategy. Without guardrails, that dynamic could spread rapidly across industries before institutions have time to respond.

At the same time, Hinton has pointed out that history shows technological shocks can be softened when societies invest early in education, retraining, and social safety nets. Policies that support reskilling, protect workers during transitions, and encourage the creation of new kinds of work could still alter the trajectory.

Still, his underlying message remains stark. The labor market shock from AI is no longer a distant or theoretical concern discussed only in academic papers. It is beginning to surface in corporate hiring data, layoff announcements, and changing job requirements. If current trends continue unchecked, 2026 may be remembered as the year economic growth stopped reliably producing jobs, forcing governments and businesses to confront fundamental questions about work, income, and the structure of modern economies.

Discussion